The Bird’s Word Blog

Tracing History on Silk Road Tours

In September and October 2017, world history teacher and avid traveler Coco Rae led two Silk Road tours for Journeys International: Tracing the Ancient Silk Route (China) and Silk Road through the Stans. Here, Coco traces the Silk Road through time, from 138 BCE through today. Read on to learn about the history experienced on these two trips.

Nothing quite conjures up the romance and allure of travel like the mention of the Silk Road. For over two thousand years, this network of trade routes crisscrossed the Eurasian continent, connecting far-flung peoples through exotic goods, innovative technologies, and spiritual and philosophical inspiration.

The Romans spoke admiringly of the mysterious “Silk People” far to the east, who filled their markets with that magnificent fabric only the wealthiest could afford; at the extravagant courts of the Chinese emperors, Byzantine glassware was admired for its fragility and grace. The Mongols galloped out of their northern steppelands and swept across the continent in either direction, making use of the age-old trails to conquer as far as Korea and Russia; itinerant monks traveled by foot and by donkey over the high passes of the Himalaya to bring the promise of Buddhist enlightenment to humble villages and great cities alike.

Every age has seen adventurers and explorers, warriors and diplomats, missionaries and merchants tread these trails, and each one brought home new stories to tell.

Zhang Qian—138 BCE

Considered by many to be the father of the Silk Road, Zhang Qian was sent westward from the imperial capital of Chang’an (modern Xi’an) by the Han emperor in an attempt to ally with the Yuezhi people of Tajikistan against the Xiongnu, a ferocious tribe with an alarming facility for devastating Chinese cities with their horse-mounted warriors. Possessing nothing like the “heavenly horses” of the Xiongnu, in an attempt to keep them out the Chinese had begun developing the fortifications that would become the Great Wall, to no avail.

The emperor loaded Zhang Qian with as much silk and other luxury goods as he could take, and gave him orders to buy any loyalties he could, drive back the Xiongnu, and return with as many horses as possible. It didn’t go well—his journey lasted twelve years, during ten of which he was held hostage by the Xiongnu. By the time he returned to China, only two of his hundred-man force remained.

But once he had escaped his captors, he traveled further west than any Chinese ever had, reaching the lands of Bactria in what is now Afghanistan, and discovering a ready market for silk and other Chinese products. He established ties with local powers, gathered extensive information about the geography, and returned home with news of lands and markets to the west.

And with that, the Silk Road was born.

Xuanzang—626 CE

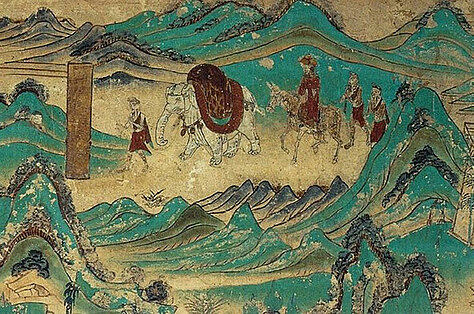

A devout Buddhist, in his early twenties Xuanzang became increasingly frustrated with the second- and third-hand Chinese translations of Sanskrit Buddhist scriptures that were all that was available in China at the time. He resolved to set out on a journey to India to gather the scriptures from the great monasteries and temples in Buddha’s native land.

He had a bit of a problem, however: the new Tang emperor, who in his hurry to take the throne, had assassinated his elder brother and forced his father to retire. In the process, he had issued an edict forbidding travel outside of China while he consolidated his power and dealt with a war along the western frontier.

Undeterred, Xuanzang decided to sneak out of the country, on foot and with only a backpack. He headed for India, passing through Tashkent and Samarkand, among other cities, along the way. After sixteen years and countless adventures that strain the imagination—which he retold himself in his Records of the Western Lands—he returned to China with a treasure trove of religious texts, statues, and implements.

Rather than punish him for breaking the imperial edict, the emperor was so grateful for what Xuanzang had done that he endowed a monastery where the now-famous monk could spend the rest of his life, translating the sutras properly and teaching others. The sutras remain to this day in the Great Goose Pagoda of Xi’an which was built for him, his adventures have been told and retold for centuries in the much-beloved Journey to the West, and his great legacy is the spread of Buddhism in China and lands to the east.

Marco Polo—1275 CE

While not the first European to travel all the way to China—a handful of hopeful Christian monks had made their way eastward in the decades prior and were received at the Mongol court—Marco Polo is certainly the most famous, due to the account of his journey he wrote on his return to Venice.

His father and uncle, both merchants, had traveled all the way to the court of Kubilai Khan while Marco was still a young boy, and had received a ready welcome (as well as realized the fortune to be made if they could bring back to Europe the fabulous goods the East had to offer). They returned to Venice when Marco was about 17, and invited him to go with them back to China.

Marco, his father, and his uncle would spend the next twenty years on the journey, much of it within China itself, and Marco’s wide-eyed account of his adventures would become the best-selling book in Europe for decades, second only to the Bible. Though he would be taunted as “Marco Milione,” or Marco of the Million Lies, as his stories of the East were too fabulous to be believed by what was still a very isolated Europe, nevertheless his tales were wildly popular.

Eventually, the possibility that his stories were true would begin to sink in, and more than one scholar has suggested that Europe’s Age of Exploration was sparked by his tales. After all, one of the very few books that Christopher Columbus took with him on his voyage was The Travels. Polo’s famous last words have inspired generations of travelers ever since: “I have only told the half of what I saw!”

Ibn Battuta—1325 CE

A native of Tangier, this young man set out on a pilgrimage to Mecca that turned into what is quite possibly the greatest journey in history. In 27 years and 75,000 miles, he visited the lands of every Muslim ruler in his day, from west Africa all the way to Malaysia, journeying by caravan and by ship, feted by kings and welcomed by peasants.

Unlike Marco Polo, however, Ibn Battuta’s tales were readily believed and used by travelers who followed in his footsteps the length and breadth of Asia, as well as by modern historians, ethnographers, and archaeologists who are indebted to his erudite and detailed accounts of the cultural practices and traditions of the myriad peoples he encountered, their artistic and architectural treasures, and their technology and scholarship.

He famously noted of the Chinese that “The care they take of travellers among them is truly surprising; and hence their country is to travellers the best and the safest: for here a man may travel alone for nine months together, with a great quantity of wealth, without the least fear.”

By the time he returned home, now nearly fifty years old, he had seen more of the world than any man alive—and may still claim that record.

Timur the Lame—1400 CE

Known to the West as Tamerlane, this descendant of the Mongol khans of Central Asia made it his life’s goal to recreate the glories of trans-Asian Mongol rule, centered on his hometown of Samarkand, once one of the greatest and most prosperous kingdoms at the heart of the Silk Road.

With nothing short of military genius, a taste for ruthlessness but also a respect for diplomacy, Timur brought lands as far west as Aleppo, as far south as Delhi, and as far east as the border of China under his control. Some scholars have argued that his campaigns were undertaken simply to enrich and beautify the city of Samarkand; certainly he spared no expense in making it one of the most magnificent cities of the age.

Artisans and craftspeople, architects and scientists, scholars and intellectuals poured in from across his vast empire to create his vision of an urban oasis filled with gardens, parks, markets, mosques, and palaces that no other city could rival. Many of his exquisite buildings, which would prove hugely influential on Islamic architecture, remain standing to this day, including the Registan, the Bibi-Khanym Mosque, and the Gur-e Amir mausoleum, where Timur himself is buried.

Aurel Stein—1900 CE

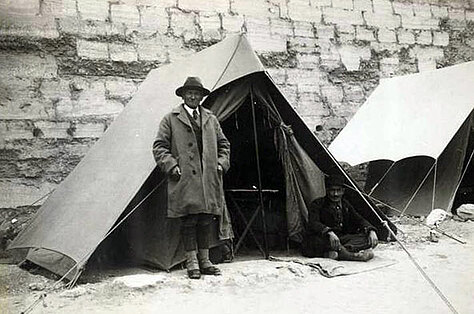

A cartographer and archaeologist, fluent in Sanskrit and steeped in the history of the Silk Road, Aurel Stein was sent out on mapping expeditions under the auspices of the British Royal Government in India to chart the ancient sites in the regions of Kashgar and along the Gansu Corridor, the old route into China that crossed the Taklimakan Desert (whose name, roughly translated, means “You go in but you don’t come out”).

While the scholarly work was certainly valid and critically important for a region that had long since fallen away from the centers of world power, his efforts were also an extension of the Great Game being played to ever more tense effect by the powers of Europe in the years before World War I.

Despite the dual and potentially dangerous nature of his work, Stein was first and foremost a student of the Road, and over years of expedition and much hardship he produced a prolific body of work that illuminated the long-lost history and cultures of the Central Asian lands, as well as preserved innumerable artifacts covering nearly the entire history of Eurasia.

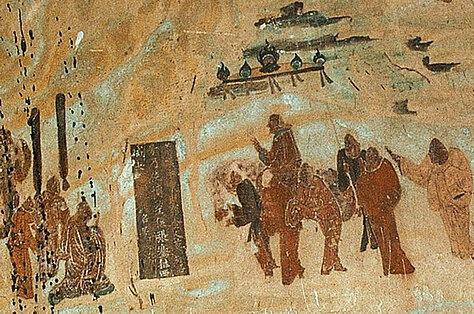

His most famous discovery was that of the “Cave of the Thousand Buddhas” in Dunhuang, which had been the last outpost of civilization before the hardships of the ancient Silk Road began for travelers. Shown the cave (and many others) by Wang Yuanlu, a Daoist monk who had appointed himself the guardian of this vast treasure, Stein was astonished by what he saw. Countless frescoes painted over centuries by travelers grateful to have survived their journeys, or fearful of the road ahead and praying for protection; thousands upon thousands of priceless manuscripts in every language imaginable; and prints, silks, brocades, sculptures, and religious offerings of every kind.

Today, the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang are a reminder of the shared heritage of Eurasian cultures, and a testament to the long history of exchange between East and West.

…And Perhaps You—2018 CE

While caravans of hundreds of camels laden with goods may no longer plod along the trade routes, and while ambitious kings may no longer dream of expansion across the wide plains of Central Asia, the lands of the Silk Road continue to beckon adventurous travelers with a taste for the romance and history of this part of the world.

From Chang’an to Constantinople, from Bukhara to Baghdad, and along secondary routes that radiated in every direction, the lands traversed by the Silk Road have for over two millennia been the heart of geopolitics, globalized trade, and cultural exchange. The footsteps of these hardy travelers continue to echo, and it is the rare modern traveler who follows them. Those who do, never forget what they see.

As Ibn Battuta wrote, “Traveling—it leaves you speechless, then turns you into a storyteller.’” That has certainly been the case for me, and if you go for yourself, I’m sure it will an epic, once-in-a-lifetime adventure on which you gather some stories of your own.

Design an adventure with Journeys International!

With over 40 years of experience, we create experiences that match your goals.

Start Planning